Oil Prices in 2023

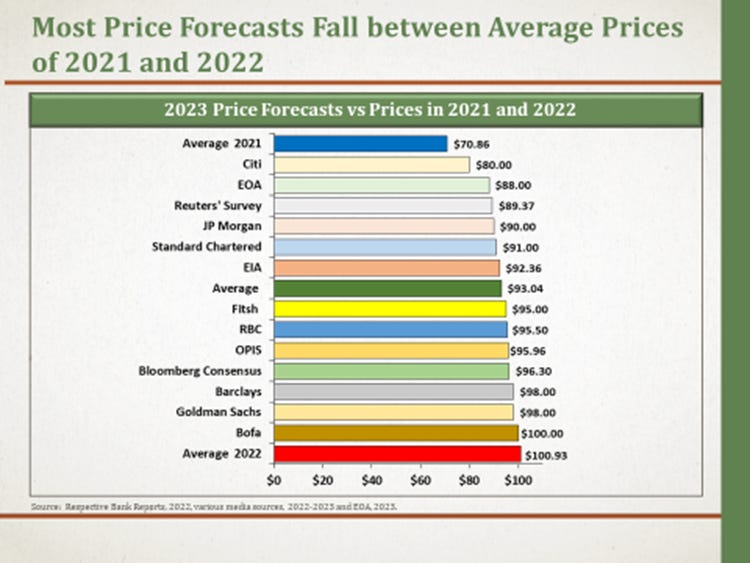

Two points stand out when looking at various price forecasts for Brent crude oil:

Most forecasts for the average Brent price in 2023 fall between the average prices of 2021 and 2022.

Some groups have “predicted prices in 2023 to be between $80/b and $100/b”. This forecast, however, is of no real value because it covers every forecast shown in Figure (5) below.

Based on our above-mentioned views on oil supply and demand, along with the issues discussed in the following section, we estimate Brent prices to average $88/b in 2023, which is next to the lowest in the list of forecasts in Figure (5).

The oil market is expected to remain weak in the first half of 2023, mainly in the first quarter. While we are bullish on the second half, especially in the second quarter of it, low prices in the first half will weigh on the average price for the whole year. In case of a recession in the first half, or even a decline in outputs for 3-4 months, oil prices will decline further. OPEC’s reaction is expected to be supportive, but not enough to raise prices to $100/b as we discuss below.

Figure (5)

Major Issues and Concerns to Watch in 2023

We discuss below four key issues related to OPEC/OPEC+ measures, Russian oil production and exports, refilling the US SPR, and others that could challenge our forecasts.

1- Will OPEC/OPEC+ Meet Soon for Additional Output Cuts?

The OPEC ministerial meeting is not expected to take place before June 4, 2023. However, during their meeting on December 4, 2022, OPEC+ ministers adjusted “the frequency of the monthly meetings to become every two months for the Joint Ministerial Monitoring Committee (JMMC) and the authority of the JMMC to hold additional meetings, or to request an OPEC and non-OPEC Ministerial Meeting at any time to address market developments if necessary.”

If oil prices continue to decline, OPEC+ has two choices: either the JMMC calls for an emergency meeting or waits for the JMMC recommendation in February.

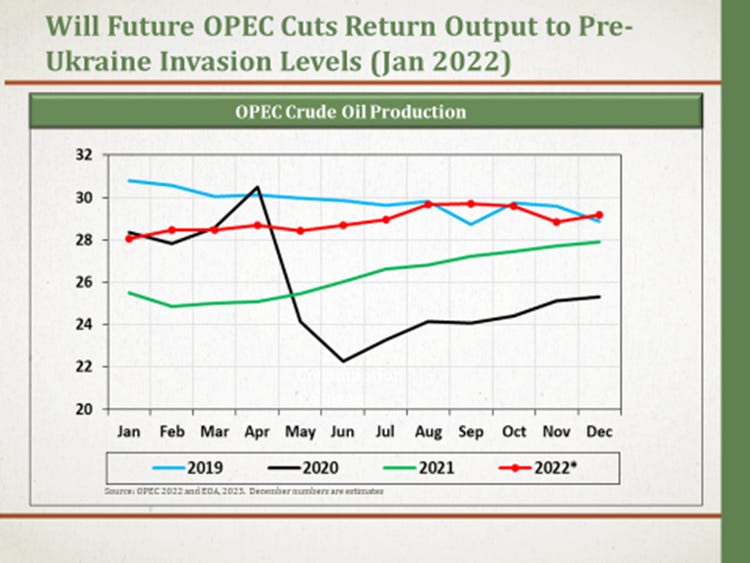

If the JMMC calls for a full ministerial meeting, this could signal that OPEC+ ministers will most likely convene to agree on a production cut. We believe that any cut will NOT be aggressive, and its role will most likely be directed at preventing a large build in global oil inventories, and indirectly maintaining Brent crude oil prices above $75/b. Any cut will return oil production to levels last seen before Russia invaded Ukraine (see Figure 6 below).

It is also worth noting that a production cut isn’t necessarily made to increase oil prices. Preventing oil prices from declining further is a successful action on its own.

In case of a recession, global or regional, we predict that OPEC/OPEC+ will agree on a large production cut. We also believe that OPEC/OPEC+ will defend a price floor of $60/b (Brent).

Figure (6)

2- Will Russian Oil Production and Exports Decline Significantly in 2023?

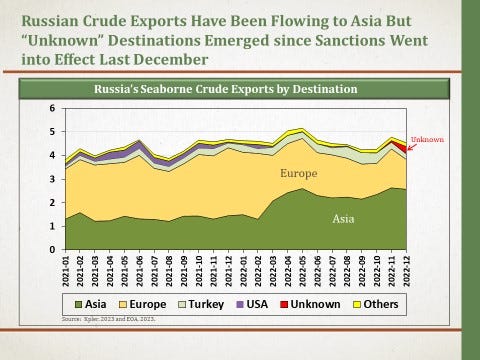

In our previous newsletters, we covered western sanctions and the G7-led price cap on Russian oil, noting that the impact of these restrictions will be limited. We said that Russian oil companies could divert part of their oil shipments, which used to be exported to Europe, to other countries as shown in Figure (7) below. But some Russian crude will still reach Europe through different means. Based on our calculations, we believe that Russian companies will have a serious problem selling between 300,000 b/d and 400,000 b/d. This conclusion is supported by the fact that some shipments have unknown destinations, as shown in the red area in the chart below.

While western sanctions will NOT sharply reduce Russian oil production and exports (in fact the price cap legalized all Russian exports since they are sold below the $60 price cap), lower oil prices will be troubling for Russian oil companies and the government’s budget. Recent reports indicated that Russia’s flagship Urals crude oil was sold in the high $30s. The breakeven is about $55/b, and about half of this cost is government taxes. If the Russian government wants companies to continue exporting at such low prices, it will have to reduce taxes. Lower taxes, however, mean a large budget deficit at a time when Russia is cut off from most of the global financial system.

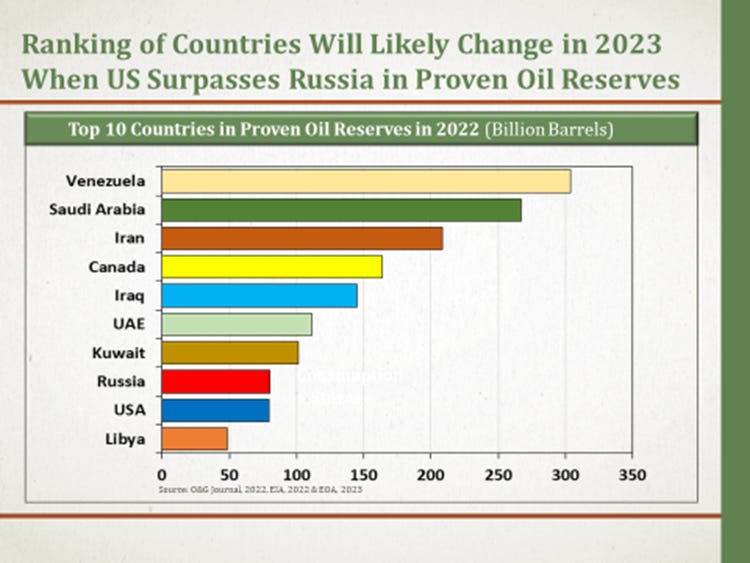

As Russia’s war in Ukraine protracts, and sanctions on Moscow deepen, lower investment and a lack of spare parts will heavily affect Russian oil production, particularly after 2023. From now until the end of the year, we expect Russian oil production to decline by about 600,000 b/d which includes the 300,000 b/d-400,000 b/d mentioned above. A decline in investments would reduce Russia’s proven oil reserves, thus allowing the US to surpass Russia as the 8th largest holder of proven oil reserves in the world. (See Figure 8 below).

Figure (7)

Figure (8)

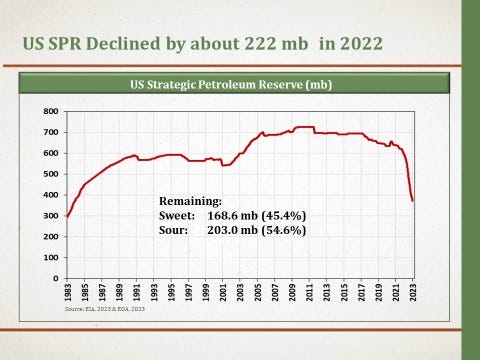

3- What is the Impact of Refilling the US SPR?

As we anticipated in our newsletter on December 18, 2022, the US administration has decided to walk away from a plan to refill the SPR with three million barrels of sour crude oil in February. The administration released about 221 mb of crude from the SPR in 2022, which included the 180 mb US President Joe Biden authorized in March 2022 (see Figure 9 below).

In our view, when the US administration decides to refill the SPR later this year the following will likely happen:

Any refill will be partial and will be around 60-90 mb, if any.

Most of the purchased amount will be medium sour crude oil, and shale producers will not benefit from this since they produce light sweet crude.

Prices for medium sour crude will be around $40 or lower.

The only way oil prices for medium sour crude oil could decline to such levels in 2023 is if we end up with a severe recession. The Administration may find a short window to purchase oil before OPEC/OPEC+ announce a cut production. In other words, the ability of the Biden administration to refill the SPR at the desired prices is in the hands of Saudi Arabia (this may be a hard truth for those who do not like to hear it).

The impact of an SPR refill, and if it happens, will be very limited. In addition to having an amount that is relatively small, buying during a period of negative sentiment creates a price floor or reduces the decline. Unlike what the US Department of Energy (DOE) has said, buying 60-90 mb of oil will not change the upstream investment decision of any oil company. Purchasing 60 mb-90 mb over a period of a few months will have no impact on offshore projects that are designed to operate for 20 years or more. In addition, most of the purchased oil may be imported or may come from the Gulf of Mexico if the US government insists on buying domestic oil.

Figure (9)

4- What Could Go Wrong with Our Forecasts?

Several factors can challenge forecasts, including changing political circumstances in oil-producing countries like Russia, Iran, and Venezuela, and natural events such as hurricanes that usually hit the US Gulf Coast. Any events that lead to changes in supply or demand would render our forecasts inaccurate. In what follows, we focus on some of these issues that have been overlooked by others, and which could invalidate our forecasts for this year.

The first issue is related to the relationship between oil, natural gas, and LNG. For example, hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico could lead to a halt in US LNG exports to Europe. In this case, LNG prices would increase substantially, forcing power companies, factories, and consumers to switch to oil products, therefore leading to a rise in oil demand to levels above existing forecasts.

A halt in LNG exports, meanwhile, will lead to lower natural gas prices in the US. Also, low and negative natural gas prices in some hubs in the US may force some oil producers to reduce production, resulting in oil production levels being lower than expected.

The second issue is regarding possible massive and extended power outages due to weather conditions or other factors. Private power generation, which uses petroleum products, increases in such circumstances, and this in its turn could raise oil demand to levels above existing forecasts. Historical evidence shows that an increase in oil demand under such conditions can reach 800,000 b/d.

The third issue is related to the possibility of a severe summer heat wave in the Middle East and North Africa that could lead to a sharp rise in demand for space cooling. Power plants in these regions usually meet this increase in demand by using fuel oil and diesel, and in some cases crude oil. In this case, there won’t only be an increase in demand, but such an increase could come at the expense of oil exports, therefore reducing global supplies while oil production is increasing. Historically, such developments have always been bullish, and for this reason, there is a possibility that the third quarter of 2023, in particular, will be bullish more than what has been expected in this outlook.

The fourth and final issue is related to US shale production growth, and crude oil quality. If most, or all the growth comes from sweet crude production and condensates, while Iran, Libya, and Nigeria increase their oil output of this same quality, the oil market will then face a surplus in this type of crude oil. Although this will depend on how refineries will react, such surplus will affect price differentials, which in turn will lead to a change in oil market balances in a way different from what has been forecasted.

In conclusion, 2023 may end up being an uneventful year for the oil market, unlike 2022 which saw unprecedented developments. However, 2023 will be the year when oil demand increases to record-breaking levels. We are also keeping an eye on the US and China: last year, we saw the US reducing its SPR while China was building it, but could 2023 be the year when China releases oil from its SPR while the US focuses on increasing its own reserves?

OIL RESERVES - WHO DO WE TRUST?

No comments:

Post a Comment